10 Common Misconceptions about Historical Thinking

Dr. Lindsay Gibson

Over the past fifty years, historical thinking has become a standard in the theory and practice of history education in Western Europe and North America before spreading globally. Since the inception of the Historical Thinking Project in 2006, historical thinking definitions, concepts, and frameworks have been included in history and social studies curriculums in most provinces and territories in Canada. All major Canadian textbook publishers have published textbooks that include historical thinking concepts, numerous history and social studies organizations have developed learning resources that focus on historical thinking, and countless Historical Thinking Summer and Winter Institutes and professional learning workshops have been held online and in person across the country.

I was first introduced to historical thinking in 2006 when I was given a copy of Teaching about Historical Thinking (I still have my original copy filled with post-it notes and dog-eared pages), which was written by Mike Denos and Dr. Roland Case and based on the historical thinking framework conceived by Dr. Peter Seixas. Since this initial introduction, I have worked with historical thinking concepts as a secondary school history and social studies teacher, a PhD student, a teacher educator working with teacher candidates and graduate students in a Faculty of Education, a curriculum and learning resources developer, and a presenter at teacher professional learning workshops and institutes. In these varied experiences, I have encountered several common misconceptions about historical thinking, which I hope to clarify below.

1 Young students cannot think historically because they don’t have enough historical knowledge.

Numerous researchers have shown that even the youngest school age students have knowledge about what happened in the past and ideas about how we know what we know about the past, some of which is accurate, and some is not. Peter Lee (2005) argues that it’s essential that educators know what ideas students have about both the content of history, but also how we know about the past so that any misconceptions they might have can be addressed.

3 Historical thinking concepts = skills.

Teachers often describe historical thinking concepts as skills, but I think they are better described as competencies. According to Roland Case (2020) competencies refer to the ability to perform effectively in a broader range of activities than skills. There are dozens of specific communication and literacy skills, but competencies refer to the ability to successfully complete an interconnected cluster of products or performances. Similarly, each historical thinking concept is comprised of interrelated disciplinary knowledge, dispositions, and skills. For example, Seixas and Morton (2013) identify five or more “guideposts” that outline the disciplinary and skills for each of the six historical thinking concepts included in the model. Competencies also emphasize authentic performance tasks that require students to make decisions about the skills, knowledge, and dispositions that are most relevant and useful for addressing real-world historical problems and issues. For example, asking students to decide the most appropriate response to a controversial historical statue in their community requires them to draw on a wide range of knowledge, skills, values, and dispositions focused on different historical thinking concepts including evidence and interpretations, historical perspective, and ethical judgments.

5 Historical thinking helps determine the objective

truth about the past.

Objective truth in history is a slippery and contested idea. A historical statement or assertion is believed to be objectively true if it meets truth conditions free from individual subjectivities (e.g., perceptions, emotions, or imagination). There are indisputable historical facts, but doing history requires more than establishing historical facts and organizing them into narratives. The past is gone and cannot be recreated, and historical narratives are constructed by humans with diverse subjectivities. It is impossible to definitively prove that any interpretation of the past is the “objective truth.” Historical thinking focuses on teaching students to analyze and interpret historical evidence to construct, deconstruct, and reconstruct historical narratives. The goal is not to establish objective truth, but to negotiate plausible solutions to the problems, tensions, and difficulties that are inherent in doing history and raised by historical thinking concepts. What events and people from the past are important to learn about? What caused historical events to occur and what are the consequences? Which interpretations of the past are most plausible? How do we make sense of similarities and differences over time? How do we understand what people thought and believed in the past? How should we respond to injustices and heroic actions in the past?

7 Teachers and students shouldn’t judge the past by the standards of the present.

When discussing historical injustices, some people argue that we shouldn’t judge those in the past using standards of the present. Interestingly, the same argument is not applied when discussing people in the past who deserve to be honoured in the present. Surely it’s important to understand the historical context, perspectives, values, worldviews, and beliefs of people in the past before making judgments. At the same time, we are inescapably located in the present, and it is impossible to avoid making judgments about the past. Every time teachers make a decision about what to teach about (or not to teach about) they are making judgments about the past. When we make ethical judgments about past transgressions, it is important to understand what occurred before, during, and after the historical event; the social, political, cultural, and ethical norms that existed at the time; the circumstances, constraints, options, and motivations that initiated or limited historical people’s actions; and the values, beliefs, attitudes, and intellectual frameworks that different people held about what was considered ethical (Gibson et al., 2022).

9 Primary sources are more useful than secondary sources for teaching historical thinking.

Primary sources are original or first-hand in terms of time and access to the historical topic being investigated. Secondary sources are second-hand in that they are produced from evidence drawn from other primary and secondary sources. Determining whether a source is primary or secondary depends on the question being asked. A statue and plaque built to commemorate a significant historical event is a secondary source if the question is focused on what happened during the battle, but a primary source if the question is focused on what the people who created the statue thought about the historical event. During professional learning sessions I regularly ask pre- and in-service teachers if primary sources are more useful than secondary sources for teaching historical thinking? In most cases participants say that primary sources are more useful because they were created at or close to the time and location of the topic being investigated. Occasionally participants respond with “neither” or “both,” which are both plausible answers. All primary and secondary sources need to be closely scrutinized and analyzed in relation to the historical question and purpose of our investigation, and so neither is fundamentally more useful. Alternatively, both types of sources are useful because responding to a historical research question requires analysis of both primary sources and the interpretations and narratives included in secondary sources.

2 There is widespread agreement about the key concepts that constitute HT.

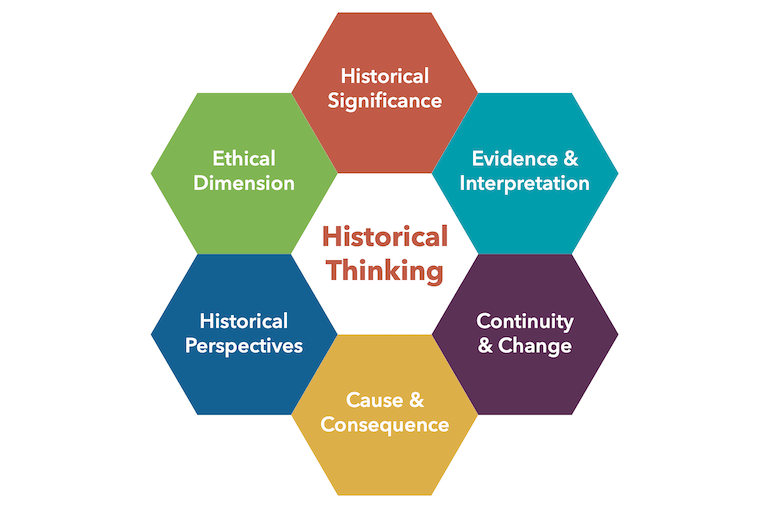

Historical thinking has a complex and contested nature, and there are several conceptual models and approaches to historical thinking that include some of the same but also different historical thinking concepts. Sam Wineburg (1999) identified four heuristics—sourcing, contextualization, corroboration, and close-reading to provide teachers with practical tools for teaching and assessing students’ historical literacy and historical thinking about evidence. In Canada, Peter Seixas’ (2009) defined historical thinking in terms of six historical thinking concepts: historical significance, evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspectives, and the ethical dimension. Scholars have also called for more focus on additional historical thinking concepts, including historical empathy (Endacott & Brooks, 2018) and historical interpretations/narratives (Chapman, 2017).

4 Historical thinking “skills” are more important than historical content knowledge.

There has been an interminable debate amongst history and social studies educators about skills versus content. Advocates of teaching skills argue that historical information can be looked up on their phones, and students should be taught the skills to identify and analyze historical information rather than learn historical information. Those who argue for the importance of content knowledge maintain that students need to learn foundational knowledge before they can think historically about it. This debate is based on a false dichotomy. Thinking historically without historical content is meaningless, if not impossible, and learning historical content without understanding how it is produced can undermine students’ understanding of both the nature of history and historical content.

6 Historical thinking is apolitical and uncritical.

Several scholars have criticized historical thinking for being depoliticized and uncritical in that it fails to address the relationships between power, knowledge, ways of knowing and the social relations, identities, and subjectivities they help foster and normalize (Cutrara, 2009; Parkes, 2009; Segall, 2006). Critical scholars have also challenged historical thinking approaches for not being sufficiently attentive to the ways that students’ cultural, ethnic, gender, religious, and disability identities shape their historical understandings (Crocco, 2018; Segall et al., 2018). Historical thinking can undoubtedly be used in an uncritical way that reinforces current inequalities and injustices, but it also has the potential to make important contributions in terms of conceptualizing the tools, processes, and ways of thinking that help students make sense of who they are, where they stand, and what they can do—as individuals, as members of multiple, intersecting groups, and as citizens with roles and responsibilities in relation to nations and states in a complex, conflict- ridden, and rapidly changing world.

8 Historical information = historical evidence.

Historical evidence refers to the relevant, credible inferences that are made from primary and secondary sources that are used to answer a question about the past. Historical information only becomes evidence when it is used to respond to a historical question. If students list dates, or recall facts about past events they are presenting information, not evidence. Historical information becomes evidence when students employ it to offer an interpretive conclusion, explanation, or judgment. For example, the statement that the Canadian government collected $23 million in head taxes from approximately 81,000 Chinese immigrants is historical information. The statement becomes evidence when it is used to make a conclusion or argument. For example, claiming that descendants of Chinese immigrants deserve compensation from the Canadian government because $23 million in head taxes were collected transforms information into evidence.

10 Teaching students to analyze primary and secondary sourcesinvolves determining whether

the sources are biased or not.

There are two main problems with analyzing primary and secondary sources for bias. Firstly, bias is often used synonymously with perspective, point of view, and opinion, which is problematic. Bias is defined as “prejudice in favour of or against one thing, person, or group, usually in a way considered to be unfair.” Perspective is a particular attitude or way of regarding something, and point of view is the position from which something is considered or evaluated. People’s opinions are shaped by their point of view, perspectives, beliefs, attitudes, and values, but they are not biased unless they unfairly prejudge or favor something over another. Having an opinion does not indicate bias, unless evidence is unfairly judged or particular perspectives and opinions are excluded. The second issue with having students analyze evidence for bias is that it impedes their historical thinking in that it reinforces the problematic understanding that there are unbiased sources available, and biased sources should be avoided or discarded. In many cases, the most “biased” (prejudicial) sources are often the most interesting and useful sources because they provide important insights to the attitudes, beliefs, and worldviews of those who created them. Additionally, asking students to identify bias in some types of primary sources makes no sense. For example, one cannot ask whether primary source traces, remnants of the past that were not created to describe or explain the past) such as natural records (e.g., fossils and culturally-modified trees) and artifacts and documents (e.g., tools, and train schedules) are biased. Rather than teach students to identify bias, a more helpful approach is to invite students to source and contextualize the source to make inferences about who created it.

1 Young students cannot think historically because they don’t have enough historical knowledge.

Numerous researchers have shown that even the youngest school age students have knowledge about what happened in the past and ideas about how we know what we know about the past, some of which is accurate, and some is not. Peter Lee (2005) argues that it’s essential that educators know what ideas students have about both the content of history, but also how we know about the past so that any misconceptions they might have can be addressed.

2 There is widespread agreement about the key concepts that constitute HT.

Historical thinking has a complex and contested nature, and there are several conceptual models and approaches to historical thinking that include some of the same but also different historical thinking concepts. Sam Wineburg (1999) identified four heuristics—sourcing, contextualization, corroboration, and close-reading to provide teachers with practical tools for teaching and assessing students’ historical literacy and historical thinking about evidence. In Canada, Peter Seixas’ (2009) defined historical thinking in terms of six historical thinking concepts: historical significance, evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspectives, and the ethical dimension. Scholars have also called for more focus on additional historical thinking concepts, including historical empathy (Endacott & Brooks, 2018) and historical interpretations/narratives (Chapman, 2017).

3 Historical thinking concepts = skills.

Teachers often describe historical thinking concepts as skills, but I think they are better described as competencies. According to Roland Case (2020) competencies refer to the ability to perform effectively in a broader range of activities than skills. There are dozens of specific communication and literacy skills, but competencies refer to the ability to successfully complete an interconnected cluster of products or performances. Similarly, each historical thinking concept is comprised of interrelated disciplinary knowledge, dispositions, and skills. For example, Seixas and Morton (2013) identify five or more “guideposts” that outline the disciplinary and skills for each of the six historical thinking concepts included in the model. Competencies also emphasize authentic performance tasks that require students to make decisions about the skills, knowledge, and dispositions that are most relevant and useful for addressing real-world historical problems and issues. For example, asking students to decide the most appropriate response to a controversial historical statue in their community requires them to draw on a wide range of knowledge, skills, values, and dispositions focused on different historical thinking concepts including evidence and interpretations, historical perspective, and ethical judgments.

4 Historical thinking “skills” are more important than historical content knowledge.

There has been an interminable debate amongst history and social studies educators about skills versus content. Advocates of teaching skills argue that historical information can be looked up on their phones, and students should be taught the skills to identify and analyze historical information rather than learn historical information. Those who argue for the importance of content knowledge maintain that students need to learn foundational knowledge before they can think historically about it. This debate is based on a false dichotomy. Thinking historically without historical content is meaningless, if not impossible, and learning historical content without understanding how it is produced can undermine students’ understanding of both the nature of history and historical content.

5 Historical thinking helps determine the objective truth about the past.

Objective truth in history is a slippery and contested idea. A historical statement or assertion is believed to be objectively true if it meets truth conditions free from individual subjectivities (e.g., perceptions, emotions, or imagination). There are indisputable historical facts, but doing history requires more than establishing historical facts and organizing them into narratives. The past is gone and cannot be recreated, and historical narratives are constructed by humans with diverse subjectivities. It is impossible to definitively prove that any interpretation of the past is the “objective truth.” Historical thinking focuses on teaching students to analyze and interpret historical evidence to construct, deconstruct, and reconstruct historical narratives. The goal is not to establish objective truth, but to negotiate plausible solutions to the problems, tensions, and difficulties that are inherent in doing history and raised by historical thinking concepts. What events and people from the past are important to learn about? What caused historical events to occur and what are the consequences? Which interpretations of the past are most plausible? How do we make sense of similarities and differences over time? How do we understand what people thought and believed in the past? How should we respond to injustices and heroic actions in the past?

6 Historical thinking is apolitical and uncritical.

Several scholars have criticized historical thinking for being depoliticized and uncritical in that it fails to address the relationships between power, knowledge, ways of knowing and the social relations, identities, and subjectivities they help foster and normalize (Cutrara, 2009; Parkes, 2009; Segall, 2006). Critical scholars have also challenged historical thinking approaches for not being sufficiently attentive to the ways that students’ cultural, ethnic, gender, religious, and disability identities shape their historical understandings (Crocco, 2018; Segall et al., 2018). Historical thinking can undoubtedly be used in an uncritical way that reinforces current inequalities and injustices, but it also has the potential to make important contributions in terms of conceptualizing the tools, processes, and ways of thinking that help students make sense of who they are, where they stand, and what they can do—as individuals, as members of multiple, intersecting groups, and as citizens with roles and responsibilities in relation to nations and states in a complex, conflict- ridden, and rapidly changing world.

7 Teachers and students shouldn’t judge the past by the standards of the present.

When discussing historical injustices, some people argue that we shouldn’t judge those in the past using standards of the present. Interestingly, the same argument is not applied when discussing people in the past who deserve to be honoured in the present. Surely it’s important to understand the historical context, perspectives, values, worldviews, and beliefs of people in the past before making judgments. At the same time, we are inescapably located in the present, and it is impossible to avoid making judgments about the past. Every time teachers make a decision about what to teach about (or not to teach about) they are making judgments about the past. When we make ethical judgments about past transgressions, it is important to understand what occurred before, during, and after the historical event; the social, political, cultural, and ethical norms that existed at the time; the circumstances, constraints, options, and motivations that initiated or limited historical people’s actions; and the values, beliefs, attitudes, and intellectual frameworks that different people held about what was considered ethical (Gibson et al., 2022).

8 Historical information = historical evidence.

Historical evidence refers to the relevant, credible inferences that are made from primary and secondary sources that are used to answer a question about the past. Historical information only becomes evidence when it is used to respond to a historical question. If students list dates, or recall facts about past events they are presenting information, not evidence. Historical information becomes evidence when students employ it to offer an interpretive conclusion, explanation, or judgment. For example, the statement that the Canadian government collected $23 million in head taxes from approximately 81,000 Chinese immigrants is historical information. The statement becomes evidence when it is used to make a conclusion or argument. For example, claiming that descendants of Chinese immigrants deserve compensation from the Canadian government because $23 million in head taxes were collected transforms information into evidence.

9 Primary sources are more useful than secondary sources for teaching historical thinking.

Primary sources are original or first-hand in terms of time and access to the historical topic being investigated. Secondary sources are second-hand in that they are produced from evidence drawn from other primary and secondary sources. Determining whether a source is primary or secondary depends on the question being asked. A statue and plaque built to commemorate a significant historical event is a secondary source if the question is focused on what happened during the battle, but a primary source if the question is focused on what the people who created the statue thought about the historical event. During professional learning sessions I regularly ask pre- and in-service teachers if primary sources are more useful than secondary sources for teaching historical thinking? In most cases participants say that primary sources are more useful because they were created at or close to the time and location of the topic being investigated. Occasionally participants respond with “neither” or “both,” which are both plausible answers. All primary and secondary sources need to be closely scrutinized and analyzed in relation to the historical question and purpose of our investigation, and so neither is fundamentally more useful. Alternatively, both types of sources are useful because responding to a historical research question requires analysis of both primary sources and the interpretations and narratives included in secondary sources.

10 Teaching students to analyze primary and secondary sourcesinvolves determining whether

the sources are biased or not.

There are two main problems with analyzing primary and secondary sources for bias. Firstly, bias is often used synonymously with perspective, point of view, and opinion, which is problematic. Bias is defined as “prejudice in favour of or against one thing, person, or group, usually in a way considered to be unfair.” Perspective is a particular attitude or way of regarding something, and point of view is the position from which something is considered or evaluated. People’s opinions are shaped by their point of view, perspectives, beliefs, attitudes, and values, but they are not biased unless they unfairly prejudge or favor something over another. Having an opinion does not indicate bias, unless evidence is unfairly judged or particular perspectives and opinions are excluded. The second issue with having students analyze evidence for bias is that it impedes their historical thinking in that it reinforces the problematic understanding that there are unbiased sources available, and biased sources should be avoided or discarded. In many cases, the most “biased” (prejudicial) sources are often the most interesting and useful sources because they provide important insights to the attitudes, beliefs, and worldviews of those who created them. Additionally, asking students to identify bias in some types of primary sources makes no sense. For example, one cannot ask whether primary source traces, remnants of the past that were not created to describe or explain the past) such as natural records (e.g., fossils and culturally-modified trees) and artifacts and documents (e.g., tools, and train schedules) are biased. Rather than teach students to identify bias, a more helpful approach is to invite students to source and contextualize the source to make inferences about who created it.

My purpose in this article is to share some of the misconceptions I’ve encountered throughout the nearly two decades I’ve been working with historical thinking. My hope is to deepen educators’ understanding of historical thinking and help them avoid making some of the mistakes I’ve made. If there are other misconceptions you’ve had or experienced, please share them via email (lindsay.gibson@ubc.ca) or twitter (@ls_gibson).

Bibliography

Case, R. (2020). Teaching for competency. In R. Case & P. Clark (Eds.), Learning to Inquire in History, Geography, and Social Studies: An Anthology for Secondary Teachers (4th ed., pp. 121–135). The Critical Thinking Consortium.

Chapman, A. (2017). Historical interpretation. In I. Davies (Eds.), Debates in history teaching. In I. Davies (Ed.), Debates in History Teaching (Second, pp. 100–112). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Crocco, M. S. (2018). Gender and sexuality in history education. In S. A. Metzger & L. McArthur Harris (Eds.), The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 335–364). Wiley-Blackwell.

Cutrara, S. (2009). To Placate or Provoke? A Critical Review of the Disciplines Approach to History Curriculum. Journal of the Canadian Association of Curriculum Studies, 7(2), 86–109.

Endacott, J. L., & Brooks, S. (2018). Historical empathy: Perspectives and responding to the past. In L. M. Harris & S. A. Metzger (Eds.), The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning (pp. 203–225). Wiley-Blackwell.

Gibson, L., Milligan, A., & Peck, C. L. (2022). Addressing the elephant in the room: Ethics as an organizing concept in history education. Historical Encounters, 9(2), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.52289/hej9.205

Lee, P. (2005). Putting principles into practice: Understanding history (S. Donovan & J. D. Bransford, Eds.; pp. 79–178). National Academies Press.

Parkes, R. J. (2009). Teaching history as historiography: Engaging narrative diversity in the curriculum. International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching, and Research, 8(2), 118–132.

Segall, A. (2006). What’s the purpose of teaching the disciplines, anyway? The case of history. In A. Segall, E. E. Heilman, & C. H. Cherryholmes (Eds.), Social studies—The next generation: Researching in the postmodern (pp. 125–139). Peter Lang.

Segall, A., Trofanenko, B. M., & Schmitt, A. J. (2018). Critical theory and history education. In L. M. Harris & S. A. Metzger (Eds.), The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning (pp. 281–309). Wiley Blackwell.

Seixas, P. (2009). A modest proposal for change in Canadian history education. Teaching History, 137, 26–30.

Wineburg, S. S. (1999). Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(7), 488–501.